Clerk Note: Mel Brook's "The Producers" had its "Spring Time for Hitler" to secure the worst Broadway show, yet profitability. My how life imitates art. Frank Zappa said "Politics is the entertainment branch of the military industrial complex."

+++

How the Haters made Trump

https://www.buzzfeed.com/mckaycoppins/how-the-haters-made-trump

By: McKay Coppins

Date: 2016-07-16

Donald Trump stood on a debate stage in downtown Detroit, surrounded by haters he was determined to dispatch: Liddle Marco to his right, Lyin’ Ted to his left, Megyn Kelly at the moderator’s table straight ahead, and — somewhere out there, in a darkened living room 1,500 miles away — me.

About 30 minutes into the debate, Kelly asked Trump to respond to a recent BuzzFeed News report about his position on immigration.

“First of all, BuzzFeed?” Trump said, waving an index finger in the air. “They were the ones that said under no circumstances will I run for president — and were they wrong.” My phone lit up with a frenzied flurry of tweets, texts, and emails, each one carrying variations of the same message: This is all your fault.

Trump was referring to a profile I’d written two years earlier in which I chronicled a couple of days spent inside the billionaire’s bubble and confidently concluded that his long-stated presidential aspirations were a sham. He had tweeted about me frequently in the weeks following its publication — often at odd hours, sometimes multiple times a day — denouncing me as a “dishonest slob” and “true garbage with no credibility.” Breitbart published an “EXCLUSIVE” with Trump and his employees claiming I’d boorishly harassed various women during my brief stay at his Palm Beach estate Mar-a-Lago. (“I don’t know how to say it — he was looking at me like I was yummy,” complained one hostess named “Bianka Pop.”) There were a lot of things about Trump’s wrathful, wounded reaction that seemed weird at the time, but in retrospect, the weirdest was that it never really ended; for two years, Trump continued to rant about how I’m a scumbag or a loser or “just another phony guy.”

Trump’s performative character assassination led to plenty of teasing from friends and colleagues about how I had inadvertently goaded Trump into running. But as his campaign gained traction, the tone started to curdle into something more…hostile. Once, after discussing Trump’s latest outrage on cable news, the host grumbled to me, “Won’t it be great when Donald Trump becomes president because you wrote a fucking BuzzFeed article daring him to run? I mean, won’t that be fucking fantastic?” I mentioned to former Obama speechwriter Jon Lovett that Trump’s candidacy had me yearning for a new beat. “So, wait a second, you get all of us into this, and now you decide it’s beneath you?” he demanded. “No, you stay ‘til it’s fucking over. The whole thing. You stay here with the rest of us until it’s done.”

What I didn’t realize at the time was that he’d felt that way his entire life — face pressed up against the window, burning with resentment, plotting his revenge.

It’s not done yet. As Trump completed his conquest of the Republican Party this year, I contemplated my supposed role in the imminent fall of the republic — retracing my steps; poring over old notes, interviews, and biographies; talking to dozens of people. What had most struck me during my two days with Trump was his sad struggle to extract even an ounce of respect from a political establishment that plainly viewed him as a sideshow. But what I didn’t realize at the time was that he’d felt this way for virtually his entire life — face pressed up against the window, longing for an invitation, burning with resentment, plotting his revenge.

I had landed on a long and esteemed list of haters and losers — spanning decades, stretching from Wharton to Wall Street to the Oval Office — who have ridiculed him, rejected him, dismissed him, mocked him, sneered at him, humiliated him — and, now, propelled him all the way to the Republican presidential nomination, with just one hater left standing between him and the nuclear launch codes.

What have we done?

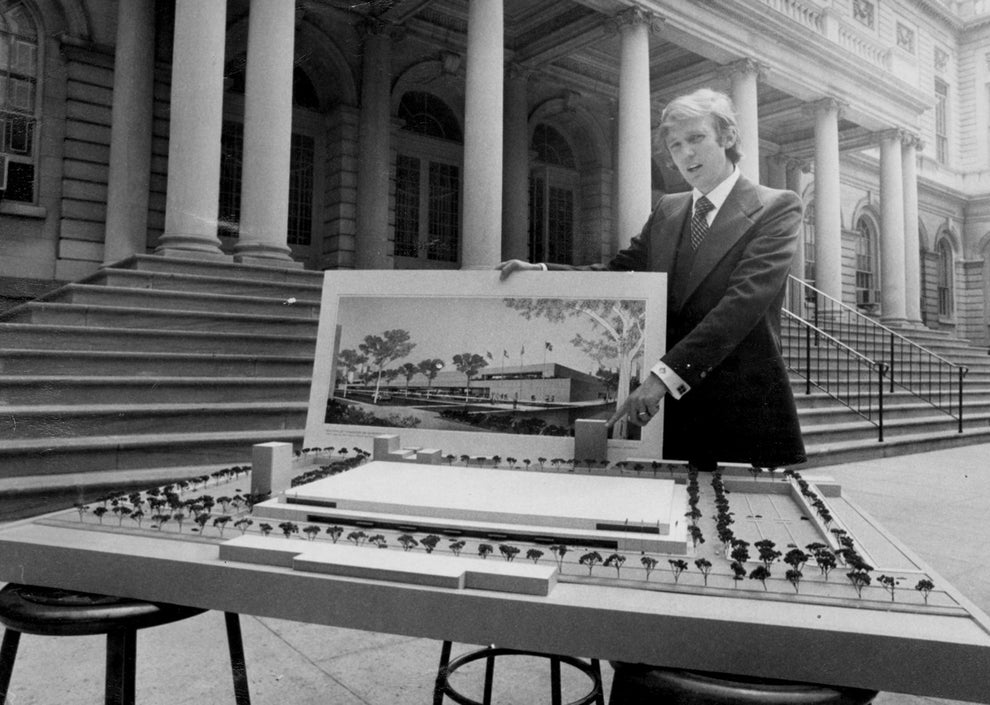

Trump at New York City Hall announcing the 34th Street Convention Center, 1977 New York Daily News Archive / Getty Images

There is a pivotal scene in the Donald J. Trump creation myth: It is 1968, and he is peering restlessly across the East River toward Manhattan. At 22, he has spent most of his life in New York’s outer boroughs — his childhood home in Queens, his father’s office in Brooklyn — and he has nothing against his native neighborhood, per se. But Donald is a man of the Ivy League now, a recent graduate of the University of Pennsylvania’s prestigious Wharton School of Finance. He is changed. And he wants more.

“Somehow, when you go to Wharton, you don’t go back,” Trump told a biographer in 2005. “It’s not a knock on Queens … [but] you go to a school like that, and you do well at the school, and you know, somehow you want to break out of that mold. I think it brought me into a different world.”

The rough-edged rich kid from Jamaica Estates had spent his teens swaggering his way through high school at an upstate military academy. But at Waspy, well-mannered Wharton, Trump’s shtick didn’t have the same winning effect. When, one day shortly after transferring to the school, he stood up in a business class and cockily declared his intention to become “the king of New York real estate,” his classmates reacted with snickers and eye-rolling.

Trump and father Fred Trump at the re-opening of Wollman Rink, 1987 New York Daily News Archive / Getty Images

With his Ivy League bachelor’s degree in hand, Trump returned home to work for his father’s decidedly non-blue-blood company in 1968. His grandfather Friedrich was a German immigrant who conned his way onto a patch of land during the Gold Rush and used it to hawk booze, hookers, and horse meat to local miners; his father Fred made his millions as a scrappy, and scandal-prone, developer who built an empire out of no-frills residential properties in New York’s working-class neighborhoods. Trump’s post-collegiate portfolio of chores included trudging through drab apartment buildings collecting rent door-to-door, usually flanked by muscled goons for protection in case the tenants got feisty. He grew bored, inevitably, and anxious.

“My father never really got away from Brooklyn and Queens,” he told Playboy in 2004. “He was very successful there, but he was more comfortable selling a piece of land in Brooklyn for $1 a foot than in Manhattan for $1,000 a foot. I used to stand on the other side of the East River and look at Manhattan.” This image, which he has evoked so many times, is foundational to the story Trump tells about himself: Manhattan as the Original Hater.

“He had enormous insecurity about his place in the world,” said Tim O’Brien, one of several Donald chroniclers over the years who have heard their subject describe some version of this scene. “I think he saw Manhattan … as the only place he could get those establishment blessings he really wanted. It’s almost an unfillable hole for him.”

“I think he saw Manhattan as the only place he could get those establishment blessings he really wanted. It’s almost an unfillable hole for him.”

Trump did eventually escape Queens at 25, renting a studio apartment on the Upper East Side, where he promptly set about sweet-talking his way into the city’s most exclusive clubs and restaurants. Trump’s goal was to expand the family business into the glitzy world of high-end Manhattan real estate while actively forging the “Donald Trump” persona — that of the high-flying, fast-talking, larger-than-life titan of industry.

To get this self-portrait painted in the press, he cultivated relationships with gossip columnists and fed tips to the tabloids about his glamorous-sounding love life. When Forbes announced it would begin publishing an annual list of the 400 richest Americans, Trump sweatily lobbied the magazine to ensure his inclusion — the beginning of a sacred Trump tradition that would continue for decades. (“We love Donald,” the Forbes 400 editors wrote in 1999. “He returns our calls. He usually pays for lunch. He even estimates his own net worth.”)

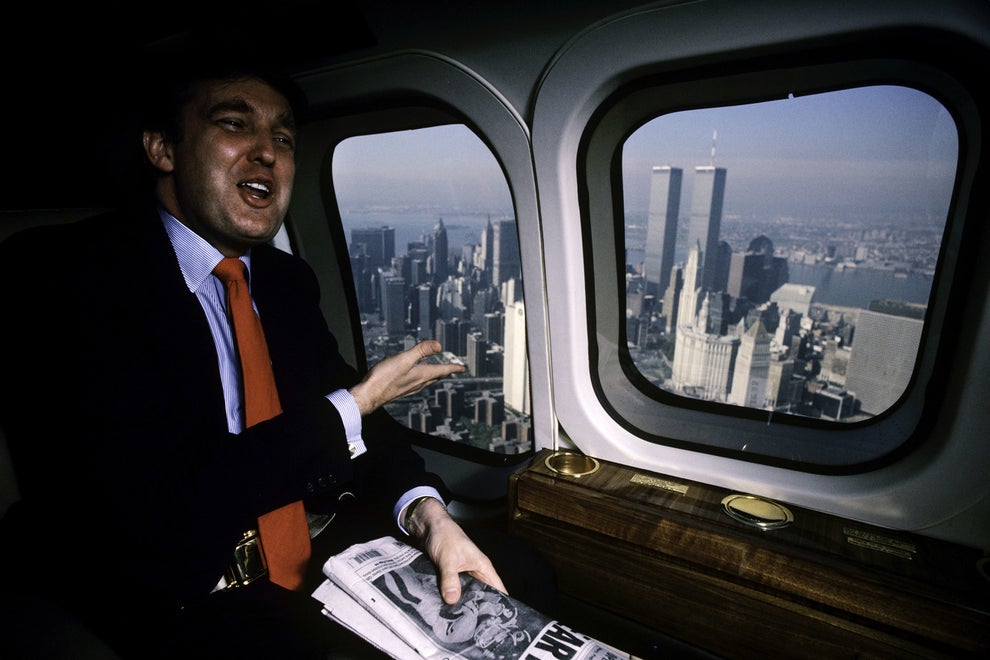

Trump in his personal helicopter above New York City in 1987. Joe Mcnally / Getty Images

In his famed 1970 New York magazine essay “Radical Chic,” Tom Wolfe compared the composition of New York City’s high society to the political history of the Caribbean — “which is to say, a revolution every 20 years.” For the new-money insurgents storming the gilded barracks, the media has always been the most powerful weapon. “The fact is that ‘Old New York’ … is no longer good copy,” Wolfe wrote, “and without publicity it has never been easy to rank as a fashionable person in New York City.” Trump understood this better than anybody. But while his skill for brazen media manipulation would serve him well in other areas, it never quite made him a “fashionable person.”

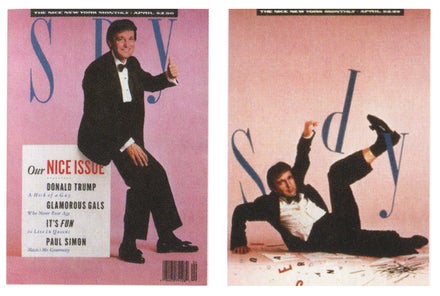

Instead, his pathological quest for coverage ended up catching the attention of the satirical magazine Spy. As soon as it launched in 1986, founding editors Kurt Andersen and Graydon Carter began mercilessly lampooning his gaudy taste, poking holes in his inflated claims to fortune, and exposing his reputation among the city’s true real estate kingpins as a JV player who was better at yapping than actually building things. In one particularly humiliating stunt, the magazine sent a series of increasingly small checks to the city’s richest people, and then reported that Trump was one of only two who bothered to deposit the one for 13 cents. Perhaps most memorably, it was Spy that first began referring to the businessman as a “short-fingered vulgarian” — one of the most enduring and effective contributions to the canon of Trump taunts.

The cover and inside cover of Spy.

Part of what made Trump such an irresistible target, Andersen recalled to me, was the “odd mixture of contempt and envy” that defined his relationship with New York’s ruling class. “Back then, there was still this idea that rich people were supposed to behave according to the old protocols of wealth,” Andersen said. “And [Trump] was this kind of bridge-and-tunnel guy who the Manhattan establishment rejected. They saw him as a guy trying to punch too far above his weight; who was rude and classless and desperate for attention, and didn’t know how to behave well.”

Of course, in reality, the Manhattan aristocracy wasn’t any more virtuous than Trump — they were just more discreet about their sins. Whereas owners of private jets commonly indulged their vanity by embedding their personal initials in the tail number, Trump preferred to stamp his name across the fuselage in giant, all-caps lettering. And while most adulterers of means had the good manners to keep their mistresses tucked away from public view, Trump was widely suspected of leaking the torrid details of his own affairs to the tabloids. “Was he the first philanderer in history? No,” Andersen said. “But he was the first to advertise it.”

Spy folded in the late ’90s, but its radical-gauche depiction of the Donald lived on as he became a mass-market phenomenon. Last year, when Trump first launched his campaign, Andersen relished watching the caricature he helped create lumber around the presidential stage. But by the time we spoke in June, he seemed somewhat more conflicted. “I think on Judgment Day,” he said, “depending on what happens, we will bear some responsibility at heaven’s gate for what we’ve done.”

Trump attends the South Florida Tax Day Tea Party Rally on April 16, 2011, in Boca Raton, Florida. Larry Marano / Getty Images

In the fall of 2010, with the national tea party wave cresting, Trump decided it was time for a rebrand. His marketing instincts had been the driving force behind a lifetime of political promiscuity, including stints as a Republican, a Democrat, an independent, and a member of Ross Perot’s Reform Party. Though he wasn’t one to read Hayek or quote Jefferson, Trump could tell there was something about this new conservative movement that was resonating with his core fanbase, and he wanted in. For guidance, Trump turned to conservative super-activist and Citizens United president David Bossie.

Two months before the midterm elections, Bossie got in touch with the Strategy Group for Media, a fast-growing Ohio-based political consulting firm that represented dozens of tea party–aligned candidates across the country. The company specialized in making lawmakers out of the right-wing rejects that had been cast off by the GOP establishment. Yet even the firm’s CEO, Rex Elsass — a man whose client roster included a semi-recent star of MTV’s Real World — balked when Bossie asked him to take a meeting with Trump in New York, according to an employee. “Why would I do that?” he responded.

They agreed to meet with Trump, but no one at Strategy Group — which was then hoping to score Mike Huckabee as their big-ticket presidential client — believed anything would come of it. “We did an hourlong Google search and found a bunch of stuff that Trump had said — on everything from abortion to guns — that probably helped him make friends on the Upper East Side, but would be toxic in courting Republican primary voters,” said Nick Everhart, who was then president of the firm.

The group’s in-house pollster quietly tested the idea of a Trump 2012 presidential bid with conservative voters in Iowa and New Hampshire, but the response was disastrously, hilariously negative. Everhart recalled huddling with Elsass after they looked through the numbers, and his boss fretting, “I can’t take this to him. He’ll throw me out of his office!”

Nonetheless, he trekked up to Trump Tower. At Everhart’s suggestion, Elsass bluntly laid out the abysmal findings of their poll and told him his only path to conservative credibility was a deliberate series of high-profile mea culpas on several hot-button issues.

Soon, political reporters started to hear rumors that someone had put a Trump 2012 poll into the field, and by the beginning of October, Trump was on MSNBC actively stoking the speculation. When Joe Scarborough asked him about the poll, Trump claimed to know nothing about it, but then added, “The results were very positive for Trump!” Watching the interview back at their office in Columbus, everyone at Strategy Group dissolved into laughter.

“Half of the story here is the dismissiveness that the political operative class had toward him.”

I asked Everhart recently if he ever had any inkling that Trump might one day capture the GOP presidential nomination: “No. Never. Nope. No way.” In retrospect, he added, that turned out to be one of the candidate’s great advantages. “Half of the story here is the dismissiveness that the political operative class had toward him.”

But when I then asked if he felt any sense of complicity in Trump’s rise, Everhart grew quiet. “Damn, that’s loaded.” He admitted that if he could have seen the future, he would have handled the 2010 meeting differently. But as it turned out, he said, the billionaire didn’t need any help connecting with the people who were flocking to tea party rallies at the time.

“[They] were not ideological conservatives — they were just mad and they felt disrespected,” Everhart said. “It was not unlike the Trump brand-marketing demo: Think of a guy who has a small subcontracting business or something. Maybe he went to college, maybe he didn’t; maybe he was in the military for a while. He’s done pretty well in life but he’s never felt respected. Nobody ever looked at him like he was a winner. That’s exactly who Trump has made millions off of. That’s exactly who Trump is.”

Trump on The View, March 2011. ABC / Via realclearpolitics.com

“Are you a birther, Donald?” Joy Behar demanded.

It was late March 2011, and Trump was sitting center-couch on the set of The View, clearly not liking the tone of this question.

“Let me just tell you,” Trump said, “I was a really good student at the best school. I’m, like, a smart guy, OK? They make these birthers into the worst idiots.” He then proceeded to lay out his just-askin’-questions case for why the sitting president of the United States might be a fraudulent foreigner engaged in a massive conspiracy to cover up his Kenyan birthplace.

While the conspiracy theory was not a hit with the ladies of The View, it delighted conservative voters and cable news bookers alike — and soon Trump found himself climbing in the hypothetical 2012 presidential polls. Hoping the publicity would buoy ratings for The Celebrity Apprentice, Trump did everything he could to keep the will-he-or-won’t-he show running through May sweeps. But the longer he kept up the pretense, the more uninhibited the public mockery and late-show monologues became.

The ridicule reached a peak on April 27, 2011, when Barack Obama held a White House press conference to unveil his long-form birth certificate — and trash Trump (without naming him) for propagating the birther nonsense. “We’re not going to be able to solve our problems if we get distracted by sideshows and carnival barkers,” the president said.

Trump reacted as though his forcing the release of the presidential birth certificate was an achievement worthy of Mount Rushmore. “He only did it because of Trump!” he crowed to reporters. But if he was embarrassed by the outrage over his quest, he could take solace knowing he would soon be attending the White House Correspondents’ Dinner as the honored guest of the Washington Post — the billionaire belle of the ball at the capital’s most exclusive social event of the season.

He arrived at the Washington Hilton on the night of the dinner, and whilethe political paparazzi clamored for photos, someone asked him how many jokes he thought the president would make about him in his speech. “I wouldn’t think he would address me,” Trump said, before striding off down the red carpet with Melania on his arm, giving no indication that he knew he was walking into an ambush.

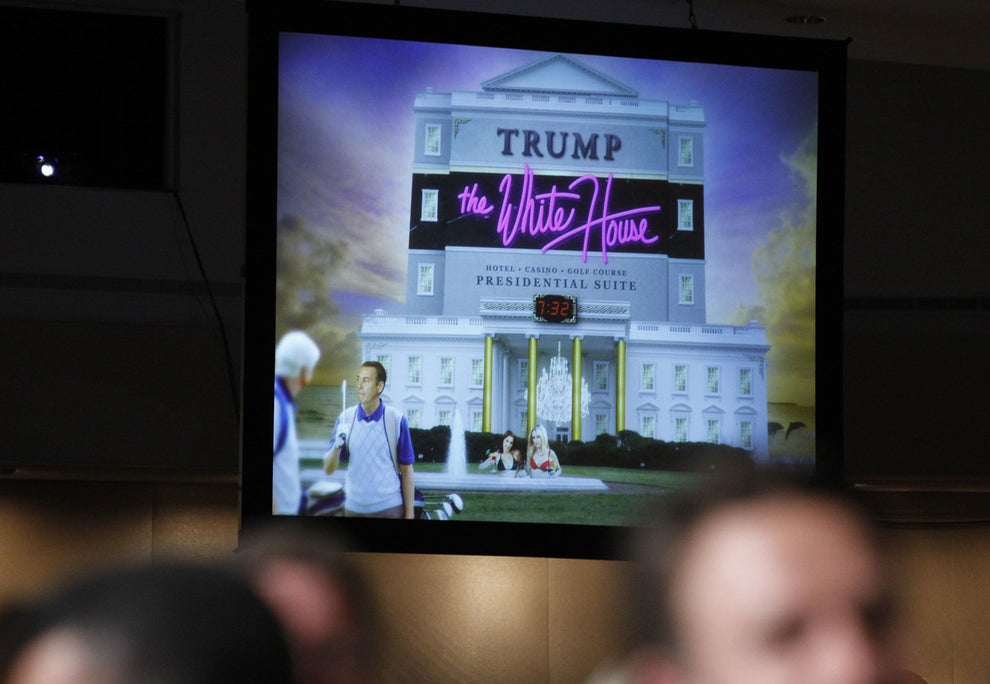

A video shown during the White House Correspondents’ Association Dinner in Washington, D.C., April 30, 2011. Manuel Balce Ceneta / AP

President Obama didn’t set out to humiliate Trump that night — at least not at first. His initial preference was to ignore the Donald, said former White House speechwriter Jon Favreau. “Like everyone else, the president didn’t take him super seriously back then. He sort of thought, ‘This is another silly thing I have to deal with in a parade of silly things.’” But after weeks of watching the news media ignore pressing political issues in favor of a walking WorldNetDaily article, Obama was grumpy — and eager for payback. As Favreau put it, “I think the circus-like quality of the situation we were in sort of egged the president on.”

In the run-up to the dinner, Favreau and another speechwriter, Jon Lovett, cycled through dozens of potential Trump jokes for Obama’s speech. Lovett finally struck gold a couple days before the dinner, while riffing over the phone with filmmaker Judd Apatow. The two speechwriters rushed to the Oval Office with a draft in hand and asked the president to try it out. They worried the president might veto it for being too caustic. But after reading it through, Obama declared it one of the best jokes they’d brought him.

Trump and wife Melania make their way to the White House Correspondents’ Dinner. Jahi Chikwendiu / The Washington Post

On the night of the dinner, Trump took his seat at the center of the ballroom, perfectly situated so that all 2,500 lawmakers, movie stars, journalists, and politicos in attendance could see him. He schmoozed and bragged and glad-handed and backslapped his way through four courses, reminding everyone who would listen that he was here “with Lally” (as in Washington Post heiress Lally Weymouth). But as soon as the plates were cleared and the program began, it became agonizingly clear that Trump was not royalty in this room: He was the court jester.

The president used his speech to pummel Trump with one punchline after another, then delivered Apatow’s haymaker in a droll deadpan.

“Obviously, we all know about your credentials and breadth of experience,” Obama said, immediately prompting laughter from the crowd. “For example, just recently, in an episode of Celebrity Apprentice [laughter] at the steakhouse, the men’s cooking team did not impress the judges from Omaha Steaks. And there was a lot of blame to go around. But you, Mr. Trump, recognized that the real problem was a lack of leadership. And so ultimately, you didn’t blame Lil Jon or Meat Loaf. [laughter] You fired Gary Busey. [laughter] And these are the kind of decisions that would keep me up at night. [laughter] Well handled, sir. [laughter] Well handled.”

When host Seth Meyers took the mic, he piled on with his own rat-a-tat of jokes, many of which seemed designed deliberately to inflame Trump’s outer-borough insecurities: “His whole life is models and gold leaf and marble columns, but he still sounds like a know-it-all down at the OTB.”

The longer the night went on, the more conspicuous Trump’s glower became. He didn’t offer a self-deprecating chuckle, or wave warmly at the cameras, or smile with the practiced good humor of the aristocrats and A-listers who know they must never allow themselves to appear threatened by a joke at their expense. Instead, Trump just sat there, stone-faced, stunned, simmering — Carrie at the prom covered in pig’s blood.

“If only we hadn’t made that joke, maybe we’d have peace in our time.”

Looking back on that night, Favreau and Lovett told me they were torn about having added weight to the chip on Trump’s shoulder. “I really don’t take any pleasure in Trump being the nominee, sincerely, even if it means they lose,” Lovett said. “If only we hadn’t made that joke, maybe we’d have peace in our time.”

As soon as the dinner ended, Trump and Melania beelined for the exit, with their elbow-throwing security guards clearing a path through the ballroom. By the next day, Trump would be publicly shrugging off the whole affair in interviews; laboring to exert an air of nonchalance; explaining how the onslaught of jokes was just the inevitable result of his terrific poll numbers; insisting that he quite enjoyed all the attention, but that poor Seth, on the other hand, revealed himself to be a “stutterer” who’d fumbled through his whole sad routine. Trump would even manage to add a righteous sheen of populism. “You know, the American people are really suffering and we’re all having fun at a gala,” he would tell Fox News.

But right at that moment, Trump had not yet formulated his face-saving plan. So when a reporter caught him on his way out and asked if he liked the jokes, Trump couldn’t come up with anything to say but the truth.

“No,” he replied, unusually quiet. “Not really.”

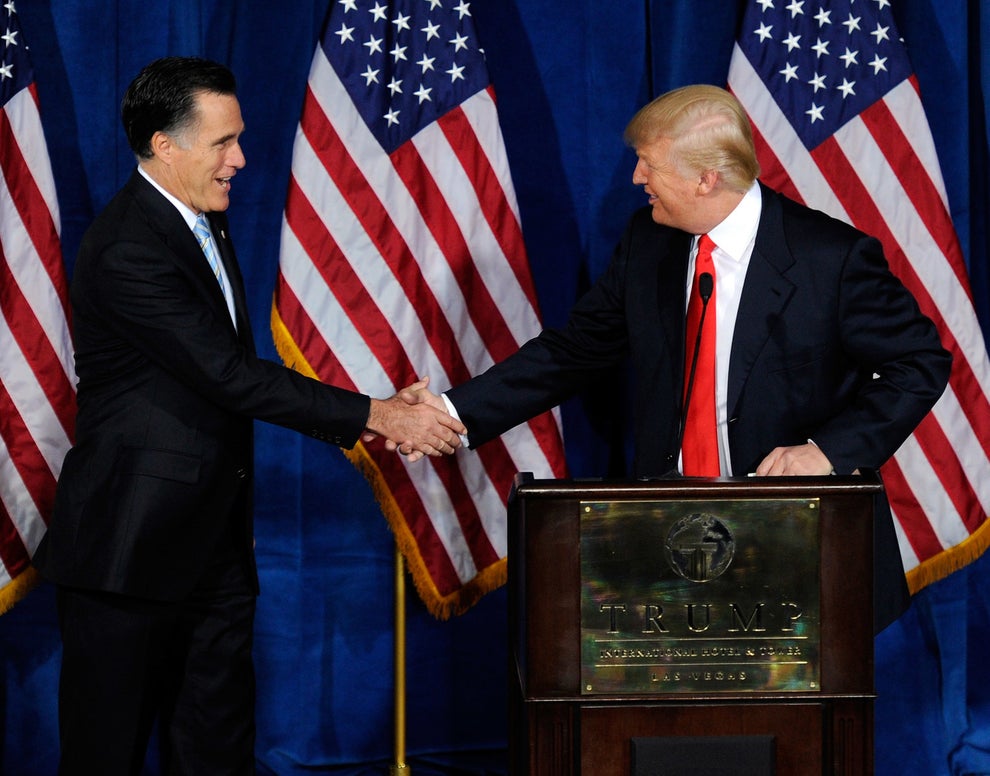

Mitt Romney and Donald Trump shake hands during a news conference held by Trump to endorse Romney for president at the Trump International Hotel & Tower Las Vegas on Feb. 2, 2012. Ethan Miller / Getty Images

A couple weeks after the dinner, Trump announced that he was bowing out of 2012 contention. Even though he was leading in “polls across the country,” he wasn’t “ready to leave the private sector” — especially his stake in “the number one show on NBC.” (That month the season finale of Celebrity Apprentice notched its worst ratings in franchise history, and a new primary poll showed Trump in fifth place.)

No matter — Trump was now in demand. His decision not to run had delivered, however fleetingly, that feeling of political A-list status that he so craved. Republican presidential prospects begin voyaging to Trump Tower to kiss his ring. Trump liked this, but it was the visit from Mitt Romney — grandee of the establishment, golden boy of the donor class — that left him feeling truly special. “We hit it off really well, better than I expected,” Trump said on CNN.

He did not know, when their meeting in Trump Tower ended, that Romney was planning to sneak out a side door so as to avoid the press; that Mitt’s campaign manager had made clear at the outset of this shameful trip that he wanted “no fucking pictures”; that the candidate’s aides would spend the rest of the day cracking jokes about the Donald’s taste in decor and patently inflated net worth.

Trump announced his endorsement of Romney in February 2012 at his Las Vegas hotel. He bragged to reporters about how hard the campaign had worked to win him over, and made a point of repeatedly plugging his hotel, which, the press learned, was “number one in Nevada” and also “the tallest building in Nevada.”

“Have you ever seen a press conference this big?” he asked Andrea Saul, the campaign’s spokeswoman and designated Trump whisperer.

“Oh, never, Mr. Trump,” she replied, suppressing a smirk. Saul and her fellow campaign staffers politely waited until he was out of earshot before they began laughing.

It went like this all through 2012, and after a while Trump started to catch on. Calls to campaign headquarters went unreturned for days. When I interviewed him in 2014, he became especially exercised as he recalled how the campaign had declined his offer to stump for Romney in Florida. “I mean, Florida?” Trump sputtered. “I do great in Florida! They love me in Florida! I employ a lot in Florida. They love me… I could have helped him carry Florida. For some reason I just kept waiting.”

But for Trump, the ultimate insult came at the Republican National Convention in Tampa. “Everybody wanted me to make a keynote speech,” Trump told me. “People were writing me thousands of letters and emails, all going crazy.” Yet despite the pleading of these vast letter-writing multitudes, the Romney campaign turned him down. Trump was indignant. “What, I wouldn’t say the right thing?” he told me. “Hey, I went to the Wharton School of Finance. I did great.” Anyway, as consolation, the campaign said he could produce a short video to show at the convention — but in the end, even that got scuttled.

“Let’s fight like hell and stop this great and disgusting injustice!”

Trump told me that Romney and his advisers were simply “afraid of me” — worried about how much less presidential Mitt would look compared to him. But people close to Trump said he has never stopped seething over the campaign’s convention snubs. “They treated him like shit,” said one confidante. (Romney emerged earlier this year as a leading spokesman of the GOP’s anti-Trump faction, but when I tried to arrange an interview with him on the subject, I was informed that he was summering with his family at their lake house in New Hampshire and would be unavailable for comment.)

As the election neared its end, Trump saw no point in trying to adhere to the Romney campaign’s rules of political propriety. In October, he made a big show of offering $5 million to Obama’s charity of choice if the president would release his college transcripts — a stunt that drew near-universal derision.

On election night, Trump bolted from the Boston hotel where the Romney campaign was holding its party as soon as it became clear that he wasn’t going to win. He had no interest in hobnobbing with haters and losers. Ascending into the sky on his helicopter, Trump dictated a series of tweets to an aide calling for mass political mutiny.

“This election is a total sham and a travesty. We are not a democracy!”

“Let’s fight like hell and stop this great and disgusting injustice!”

In early 2014, Trump was in the middle of yet another political headline-stealing spree — this time pretending to agonize over whether he should run for governor of New York later that year or hold out for a presidential bid in 2016. He had been running this old con now for a quarter century — ever since he flirted with a presidential bid in the ’80s to boost sales for The Art of the Deal — but it seemed the press was finally tired of being taken in.

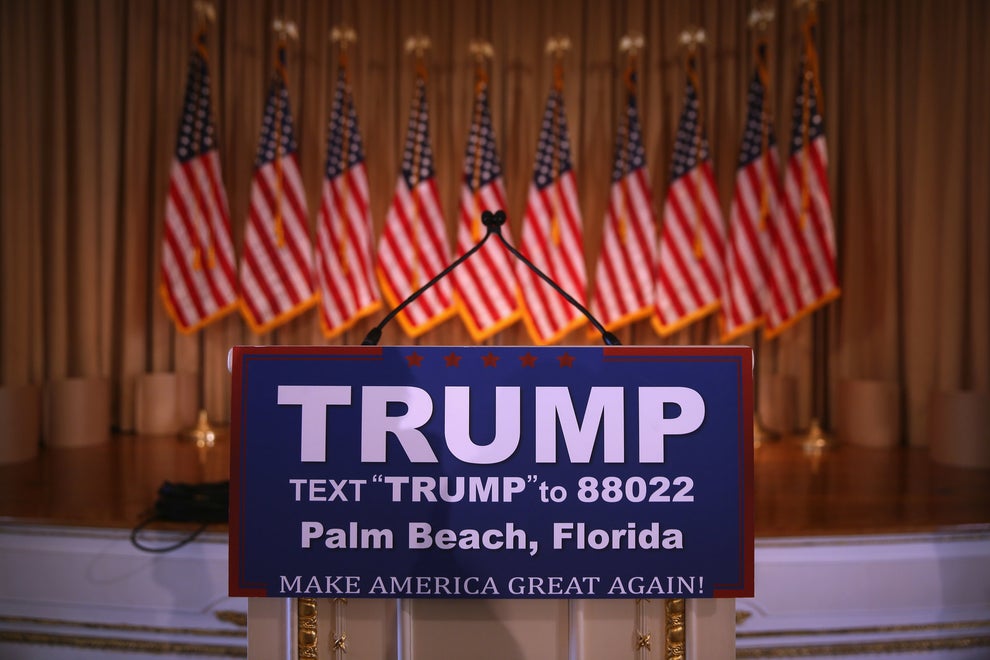

My plan was to meet up with Trump at an event in New Hampshire to witness the continuation of this charade and then fly back to New York with him — but a fluke of weather resulted in a last-minute reroute to Palm Beach. With the assistance of Sam Nunberg, a young, stocky New York native who had grown up idolizing Trump, who now worked for the billionaire’s longtime confidant and political adviser Roger Stone, I spent two accidental days at Trump’s beachside estate Mar-a-Lago and returned home with a long, weird story to tell — and perhaps an overabundance of confidence in my status as a Trumpologist. When the story came out, the headline read, “36 Hours On The Fake Campaign Trail With Donald Trump.”

Sam Nunberg NewsmaxTV / Via youtube.com

Trump’s pushback began the morning after publication, with his longtime attorney and enforcer Michael Cohen telling a reporter, “Mr. Trump is totally unfazed by this article,” followed by Trump himself posting a totally unfazed tweet: “A dishonest slob of a reporter, who doesn’t understand my sarcasm when talking about him or his wife, wrote a foolish & boring Trump ‘hit.’” Next, Trump announced he had fired Nunberg.

Re-reading the article later, I would try to determine which detail or anecdote had embarrassed Trump the most. Was it musing about the “journalistic indignity” visited upon political reporters assigned to cover him seriously? Invoking origami to describe his hair? My most generous guess was that he resented how I’d quoted him blowing off his wedding anniversary to fly to Palm Beach — a decision that prompted chuckles from Trump’s coterie of yes-men — and then described him leaning in to notify me, “There are a lot of good-looking women here.”

In fact, Nunberg later told me, my cardinal sin had been offhandedly comparing Mar-a-Lago to a “nice, if slightly dated, hotel.” As it turned out, Trump’s taste in decor was a sore spot here. When he first purchased the 17-acre Moorish estate in 1985, he intended it to signal his arrival as a card-carrying member of the Palm Beach upper crust. Instead, the town’s Waspy elite — appalled by the prospect of seeing the elegant 60-year-old mansion Trumpified and transformed into a club for his celebrity pals — fought him fiercely at every step. The result was a tangle of bitter litigation and an avalanche of snooty sniping in the society pages.

“You know, in Palm Beach there’s an in-crowd and an out-crowd and no matter how much money he has, he will never be a part of Palm Beach’s inner circle,” socialite Marlene Rathgeb told the Miami Herald in 1986, adding, “The fact that Trump is Jewish and because he’s nouveau riche turns a lot of people off.” When a rumor circulated that he’d been denied membership to the exclusive Bath & Tennis Club, Trump furiously disputed the claim, insisting even decades later, “I can get in if I wanted to. If I wanted to, I can get anything. I’m the king of Palm Beach.”

When the whole nasty ordeal was finally over and Mar-a-Lago was his, Trump looked endlessly for ways to take revenge on his stuck-up neighbors. He had DJs blast music loud enough for all the “stuffy cocksuckers” in town to hear. In 2006, he installed an 80-foot flagpole in brazen defiance of local zoning ordinances, and then left it up for six months — a towering middle finger to the Palm Beach pooh-bahs who were heaping fines on him.

My cardinal sin had been offhandedly comparing Mar-a-Lago to a “nice, if slightly dated, hotel.”

Trump had reason to feel stung by the reaction to the story: It hadn’t even been three years since every major candidate in the 2012 Republican presidential field made the trip to Trump Tower to kiss his ring, and now the future campaign managers and chief strategists for the 2016 field were openly mocking him.

Rand Paul’s chief adviser, Doug Stafford, spent an evening watching hockey and tapping out sarcastic tweets to Trump to see if he would catch on — he didn’t — and gleefully emailing me throughout the process. Two separate advisers to Marco Rubio called me to say they thought my article would finally convince party leaders they could ignore Trump now. Paul Ryan regaled me with memories from the 2012 campaign trail about dealing with the Donald, whom he’d come to regard as “an…interesting person.” Trump had already been fuming over the din of laughter coming from the political class. Now, it seemed, the din was growing louder.

When Trump rehired Nunberg (docking his pay as “punishment”), one of the aide’s first tasks was to sift through all 67 journalists who’d been credentialed to cover an upcoming conservative confab in New Hampshire where Trump was set to speak. In an internal memo written in April 2014, Nunberg meticulously combed through the list and noted which journalists the billionaire should make time for, and which ones he should avoid.

The Atlantic’s Molly Ball? “NO — VERY NEGATIVE TOWARDS MR. TRUMP.” What about Breitbart chairman Steve Bannon? “HIGH PRIORITY…MAJOR SUPPORTER OF MR. TRUMP.” Time’s Zeke Miller? “I CAN SPIN ZEKE IN BACK ON DEEP BACKGROUND.” In some cases, the notes speculated about reporters’ personal political leanings; in a couple, there was information about their romantic partners.

But no matter how vigilant Nunberg was, he told me, Trump would never let him forget that he’d been the one who let the most embarrassing story about him happen. Eventually, he said, he began using those opportunities to encourage his boss to finally pull the trigger on a presidential campaign.

“That story was bad,” Trump said one day while the two met at Trump Tower.

“Yeah,” Nunberg conceded, “but think about how bad McKay is gonna look when you run.”

Trump appeared to dwell on that for a moment, and then nodded. “That’s true.”

Microphones await the arrival of Republican presidential frontrunner Donald Trump at the Mar-a-Lago Club on March 1, 2016, in Palm Beach, Florida. John Moore / Getty Images

By the beginning of 2015, Trump had instructed his aides to start laying the groundwork for a presidential campaign — a real one.

As they deliberated over the timeline, Stone and Nunberg became enthralled with the idea of Trump launching his bid with a surprise announcement on the last day of the filing deadline. They envisioned his helicopter descending, cinematically, into New Hampshire one afternoon in late October and sending a shock wave through the Republican field. But Trump scrapped the stunt in favor of a June announcement, which would allow him to saturate the typically newsless summer media landscape — and still give him time to pull out of the race and re-up his Celebrity Apprentice contract in the fall.

“You have to understand, we didn’t think we were going to win,” Nunberg told me. “It was such a shot in the dark. Who knew?”

“You have to understand, we didn’t think we were going to win.”

Trump was starting out with a tiny political team composed mostly of misfits and mini-Trumps — Stone, Cohen, Nunberg, and the newly hired Corey Lewandowski — but he wanted his campaign operation to be so impressive-looking that no one could doubt his seriousness. One early top priority was to hire Spencer Zwick, the square-jawed fundraising wunderkind who had masterminded Mitt Romney’s campaign finance operation in 2012.

Zwick had been wooed, courted, and begged by every prospective candidate in the 2016 field, and he had politely turned down every offer — but Trump was confident he could change his mind. Over the course of 2014 and 2015, he periodically invited Zwick to meet at his 26th-floor office in Trump Tower. The setting was decidedly un-Romneysian, according to people familiar with the meetings. Leggy women in high heels tottered in and out of the room. Sometimes, a flatscreen tuned to Fox News would catch Trump’s eye and prompt him to bark out a bit of Twitter dictation to an assistant. In one meeting, Trump emphatically reminded Zwick of his vast fortune.

“I’m really rich, you know that?” Trump said.

“Yeah… I know that,” Zwick replied.

“The people who work for me are really rich too.”

“OK.”

“I can make your business big overnight.”

Zwick, who co-founded a $700 million private equity firm, was not exactly dazzled. In the world of true-life titans of industry that Zwick ran in, Trump was generally viewed as little more than a TV personality — a performer playing the part of a boardroom chieftain, and not all that convincingly. What’s more, Trump seemed to lack even a basic grasp of the political fundraising process, such as the difference between super PACs and campaigns. For a while, Zwick — whose professional life relied on a policy of never burning bridges — found ways to escape from these Trump Tower meetings without flatly rejecting him. But eventually, one day, the master deal-maker went in for the close. “Can I count on you to come raise money for us?” Trump asked.

Put on the spot, Zwick tried to ad-lib a way out. “I don’t know why you’re raising money at all,” he tried, musing that in 2012 he’d always regretted how much time Romney had to spend schmoozing fat-cat donors. Zwick proposed that Trump forget all about raising money for a while and “come out really hard and strong” with a pledge that he wouldn’t waste any time on the campaign trail sucking up to donors.

Trump was enthusiastic. “That’s a great idea!”

Trump’s tirades against the “donor puppets” would become one of the most compelling elements of his primary campaign message — that of the blue-collar billionaire who couldn’t be bought. More to the point, Zwick was off the hook. (Zwick declined to discuss the details of his meetings with Trump.)

Nunberg later confessed to me that Trump’s principled stand against the corrupt donor class was little more than lucky spin. “The truth is, he would have raised money if he could have … Donald never had any intention of self-financing.”

It was a pattern that persisted throughout 2015 as Trump and his hodgepodge team tried to assemble something resembling a presidential campaign. Often, he would start out trying to do it the traditional way — wooing rich contributors, courting conservative elites, making offers to top-flight strategists — only to find himself fumbling through yet another unfamiliar universe of taunting insiders.

While other 2016 contenders carefully strategized over how to bag billionaire mega-donors — from the Koch brothers to Paul Singer — Trump simply assumed that his status as a financial peer would do all the selling necessary, two of his former aides told me. But when he tried making his appeals to them, he was spurned — sometimes in humiliating fashion. To woo Sheldon Adelson, for instance, Trump mailed the Jewish casino magnate a booklet containing glossy photos of himself being honored at a recent Jewish gala in New York. “Sheldon, no one will be a bigger friend to Israel than me!” he wrote on it. Apparently unmoved by this gesture, Adelson instead took a liking to others such as Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio, whom his Las Vegas Review-Journal endorsed — and then leaked news of the Donald’s little memento to the Times (or at least so thought Team Trump, according to a source).

Meanwhile, the task of convincing prospective campaign staffers that he was serious this time was proving all but impossible. GOP strategist Cheri Jacobus, who entertained a possible job late in the spring of 2015, recalled raising the question with Lewandowski and realizing it was a touchy subject. “He was tired of people saying it wasn’t going to happen,” Jacobus told me. “They had a possible date in mind that was just a few weeks away, but until Trump said, ‘I’m doing it,’ I don’t think even Corey knew for sure if it would happen.”

Nunberg said Lewandowski tried, at one point, to shift blame for the recruiting failures onto him by citing my 2014 profile as a reason they couldn’t attract heavy hitters to the staff. “That article defines you,” Lewandowski told Trump, according to Nunberg.

Occasionally during this period, some rumor about Trump’s campaign-building would set off a new round of pundit chatter about his 2016 intentions — but I always firmly held my ground. Once I went on TV and blithely offered to bet a year’s salary that Trump would not appear on a ballot in Iowa.

As the date of the announcement neared, aides observed in Trump a growing agitation about his prospective presidential bid. He hemmed and hawed, talked himself in circles, changed his plans by the hour. The whole un-Trumply display kind of freaked out the employees in his orbit. “I’ve never seen him like this before,” one longtime bodyguard fretted to a colleague.

One morning in early June, Nunberg recalled, he was sitting in Trump Tower as his boss read that day’s New York Post. There was a column by conservative writer Jonah Goldberg gleefully ridiculing the Apprentice star’s 2016 prospects. “He’s a more plausible candidate than, say, Honey Boo Boo,” it read, “but that’s mostly because of constitutional age limits.” When Trump finished, he set the paper down quietly on his desk.

“Why don’t they respect me, Sam?” Trump asked.

A few days later, Trump left for a short trip to Scotland to unveil a newly renovated clubhouse at his golf course. While there, he phoned Lewandowski back in New York and said he was having second thoughts about the campaign and wanted to postpone the kickoff event. Panicked, Trump’s fledgling political team pleaded with him to stay on course. The event was just days away, and they had already promised the press it would feature a “major announcement.”

Trump’s advisers took turns making appeals to his ego, to his patriotism, to his lust for TV cameras — anything they could think of. What finally seemed to do the trick, according to Nunberg, was floating the notion that his haters might get the final word on him in the history books. “I don’t know what’s going to happen in this election,” he recalled telling Trump. “But no matter what, they’re gonna write about it a hundred years from now. And they’re never gonna be able to say you didn’t run.”

Trump adopted this as a kind of mantra in those final, anxious days before entering the race. “They’re never gonna say I didn’t run,” he recited to one aide after another. “They’re never gonna say I didn’t run.”

Trump arrives at the press event announcing his candidacy for presidency at Trump Tower on June 16, 2015, in New York City. Christopher Gregory / Getty Images

When the day of Donald Trump’s “major announcement” arrived, I was in a small New Hampshire town more than 200 miles away. Jeb Bush was there on the second stop of his campaign kickoff tour, and dozens of political journalists had crammed onto the antique theater’s creaky balcony to watch the presumed Republican frontrunner in action.

In truth, though, most of us were glued to the spectacle at Trump Tower, unfolding in a stream of baffling dispatches on Twitter — Trump gliding regally down a gold-framed escalator; the quote about the Mexican rapists; the lengthy tangent about his net worth.

Then he finally said the words: “Ladies and gentlemen, I am officially running for president of the United States!”

Trump’s advisers had tried to give the scoop on Trump’s announcement to the New York Times, but the paper declined the tip. Even at this point, many in the media wondered whether he would actually file the requisite paperwork to run. I went on TV the day after his announcement and spent most of the time laughing — a bit too loudly — at what had unfolded. In our mad rush to dismiss Trump’s chances and prosecute his intentions, one portion of the candidate’s speech seemed to escape our attention.

“I started off in a small office with my father in Brooklyn and Queens,” Trump said. “And my father said … ‘Donald, don’t go into Manhattan. That’s the big leagues. We don’t know anything about that. Don’t do it.’ I said, ‘I gotta go into Manhattan. I gotta build those big buildings. I gotta do it, Dad. I’ve gotta do it.’”

One afternoon earlier this spring, I met Sam Nunberg for lunch at Peter Luger Steakhouse in Brooklyn. We hadn’t seen each other since our star-crossed trip to Mar-a-Lago two years earlier, and he promptly apologized for his role in the Breitbart smear.

“I’ll be honest, that was me. Sorry, man,” Nunberg said. He added, “Donald loved it.”

Nunberg had been fired, again, shortly after the launch of the campaign, when his past racist Facebook posts were unearthed. In retaliation, Nunberg had endorsed Ted Cruz and publicly slammed his former boss as a man with no “coherent political ideology.” But the spurned aide still struck me as an unlikely member of Trump’s hater corps. He was no elite gatekeeper or snide skeptic, but a true believer — the very model of the campaign’s combative, starstruck audience. As we ate, Nunberg vacillated between glimmers of defiance (“It’s Donald now,” he kept correcting himself. “I’ll never call him ‘Mr. Trump’ again!”) and moments of pining (“I really do think he liked me, but Corey was his new toy”).

Still, with some distance, Nunberg could see that the campaign he’d spent years dreaming of had gone haywire. He was particularly alarmed by how the candidate seemed to promote violence at his rallies. “He started out as the Republicans’ Obama, and somehow it’s turned into Mussolini,” Nunberg lamented.

We spoke often over the next few months. Nunberg was living with his parents and getting sober; most days, he seemed focused primarily on his hell-bent crusade to take revenge on Lewandowski for getting him fired. I would often see him texting tips to reporters and taking calls — always in a clipped mafioso voice — to strategize with his fellow soldiers in Trumplandia civil war.

One day shortly after Trump clinched the Republican nomination, Nunberg seemed unusually glum. He told me that for months after he was pushed out of the campaign, he would become teary-eyed every time he passed Trump Tower. “I loved Donald like an uncle,” Nunberg said. “I’m not telling you this to sound — and I hate saying it like this, but — gay. But maybe that was the problem. Not only was I invested in the idea of him running, but I was too emotionally invested.”

It seemed inconceivable to me that Trump — a man who has been snubbed, slighted, and rejected by millions — would continue to freeze out someone who so clearly idolized him. But on July 13, news broke that Trump was suing Nunberg for $10 million over breach of his confidentiality agreement by allegedly leaking dirt on the campaign to the New York Post. Nunberg had filed his own legal action against Trump in New York courts, prompting the whole messy affair to spill into public view.

“He’s always hard on me,” Nunberg told me the night the news of the lawsuit broke. “I don’t know why. I don’t know why. But I can’t sit around wondering about it anymore.”

But while Trump’s memory is as long as his skin is thin, he is not always so unforgiving — after all, he must know that he’d be nowhere without his enemies and doubters goading him, daring him. Just days before he was to name a running mate and be officially nominated as the Republican candidate for the president of the United States, he found the time to send along this email:

McKay -

You got it all wrong, but I won’t hold it against you. Nor do you have to pay the one year salary to me that you guaranteed if I ran — I will let you off the hook. And remember not only did I run in the primaries, I won — watch what happens in the general.

Best Wishes,

Donald J. Trump

The article is reproduced in accordance with Section 107 of title 17 of the Copyright Law of the United States relating to fair-use and is for the purposes of criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, and research.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Vatic Clerk Tips: After 7 days, all comments to an article go into the moderation queue for approval which happens at least once a day. Please be patient.

Be respectful in your comments, keeping in mind that these discussions will become the Zeitgeist of our time that future database archeologists will discover. Make your comments worthy and on the founding father's level in their respectfulness, reasoning, and sound argumentation. Prove we weren't all idiots in our day and age. Comments that advocate sedition or violence are not encouraged. Racist, ad hominem, and troll-baiting comments might never see the light of day.